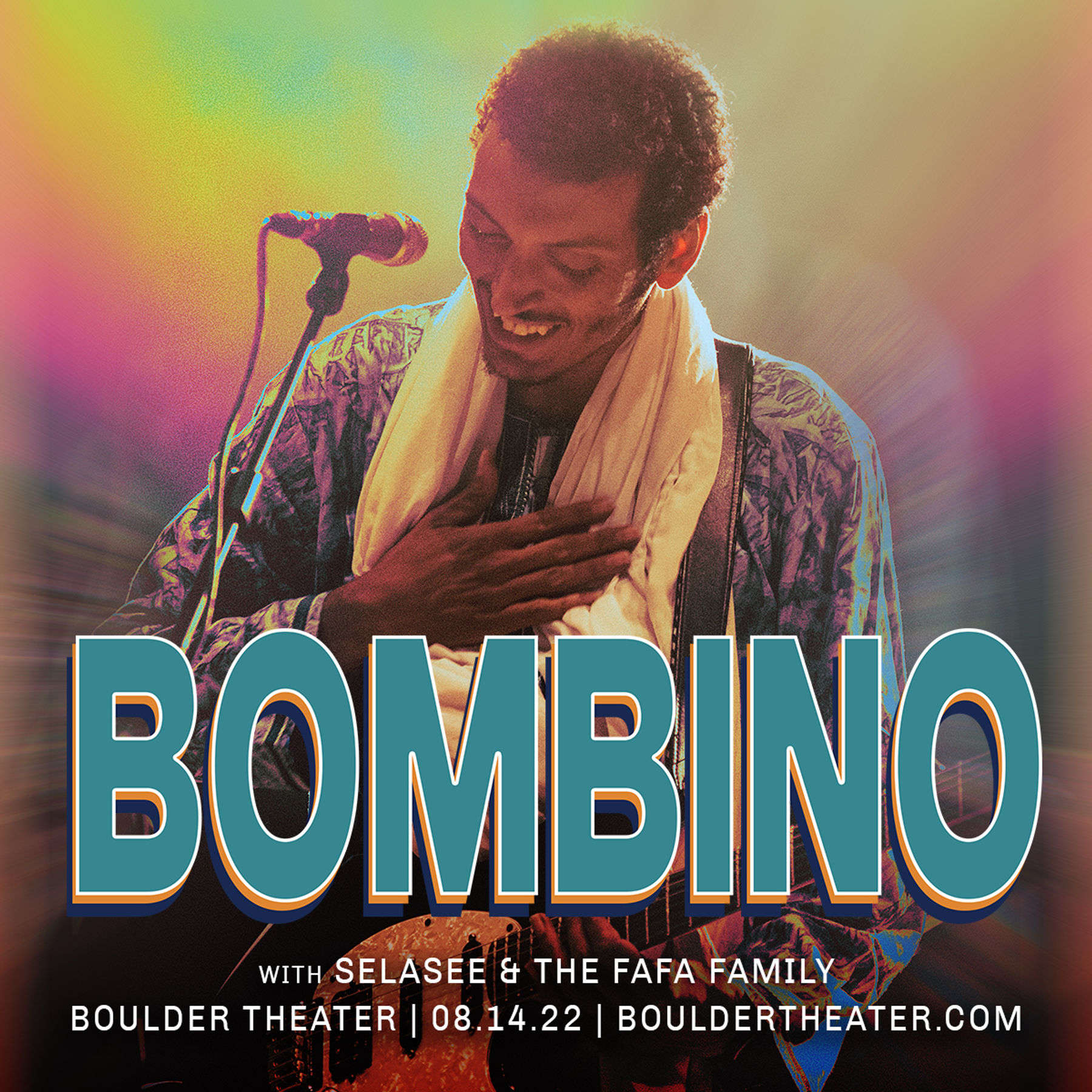

Bombino with Selasee & the Fafa Family

Categories: Arts & Entertainment Live Music

Date and Time for this Past Event

- Sunday, Aug 14, 2022 8pm - 11pm

Location

Boulder Theater

2032 14th St

Details

Home. Where the heart is. For Bombino and most other Tuareg , there’s only one place that can be. In recent years, the rest of the world has largely written off that home as a hot and savage wasteland, a bolt hole for religious extremists and terrorists, a geopolitical video nasty with little to offer apart from the oil, gold and phosphates that lie beneath its soil. But Bombino would like us to take a closer look and think again. His feelings are beautifully summed up in the song “Tehigren” (‘Trees’), from his brand new album ‘ Deran ’ : ‘Do not forget the green trees / In our valleys in the Sahara / In the shade of which, / Rest the beautiful girls / Radiant and lovable’ .

How to celebrate that desert home, how to protect it, develop it, unify it, respect it and, above all, never forget it, are the salient themes of ‘ Deran. ’ They’re dressed up in ten songs of rare maturity and power that mark a turning point in the career of a guitarist and song writer who was born in the shade of an acacia tree about eighty miles north west of the ancient town of Agadez, and has since risen to forefront of the new Tuareg guitar generation. It’s a turning back the source of everything that makes Bombino who he is.

“My mission for this album was always to get closer to Africa,” he says. Not surprising then that the decision was made to record ‘ Deran ’ as close as possible to his native Niger in the southern Sahara. The ideal venue emerged in the shape of Studio Hiba , a top flight recording facility owned by King Mohammed VI (he loves his tunes, apparently) located in a fairly drab industrial suburb of Casablanca in Morocco. There Bombino and his steady long - term band - fellow Tuareg Illias Mohammed on guitar and vocals, American Corey Wilhelm on drums and percussion and the Mauritanian ( living in Belgium ) Youba Dia on bass - slept, ate and made music in blissful isolation. Their circle was widened by Moroccan percussionist Hassan Krifa, and by Bombino’s cousins Anana ag Haroun (lead singer of the Brussels - based Tuareg band Kel Assouf), and Toulou Kiki (singer and star of the film Timbuktu), who dropped in to add some ‘gang’ vocals. After Casablanca, the tapes flew to Boston to be embellished by Sudanese friend and keyboardist Mohammed Araki.

Whatever emerged at the end of the process had to be fresh and powerful. Yes. Bombino and crew have conjured up a roving mystery tour of contemporary Saharan sounds, from the raw diesel rock of the opener ‘Imajghane’ (‘The Tuareg’ ) , to the camel gait lope of ‘Tenesse’ ( ‘ Idleness ’ ), the tender lilt of Midiwan (‘My Friends’) and the ‘ Tuareg gae’ style that is Bombino’s unique contribution to desert music on the song ‘Tehigren’. All the desert is there, harsh and gentle, tragic and playful.

But more than anything ‘Deran’ had to be honest and true. The pressure to be the authentic voice of his culture and his home on the world stage weighs heavy on Bombino. “You have to begin with the question of who you are,” he says. “You’re a Tuareg . With all the travels, all the experience of world, it’s as if I’m making myself remember where I come from. Where I come from will always be my home, my memory.”

Simple, raw, true, that was the brief. “We wanted him to take a deliberate step out of the shadow of the celebrity producer,” says Bombino’s manager, and ‘ Deran ’ producer , Eric Herman. “Apart from that, the idea was to take this raw, spontaneous, unadulterated approach to capturing his songs.”

Assembling his team on African soil was also Bombino ’s way of questioning the divisions that separate people and continents, of demonstrating “that people here aren’t against foreigners.” Back in the late 1990s, early 2000s, like so many fellow Tuareg youth, Bombino worked as a cook and guide for various tourist agencies in the deserts around Agadez. He remembers how foreign visitors would often bring guitar strings to distribute among local musicians. To budding guitarists like Bombino, those strings were more valuable than gold. Now he rues the death of Saharan tourism, killed by insecurity and conflict.

“For us, it’s a matter of breaking down barriers,” he says, “not the frontiers of a country, but the frontiers that prevent people forming relationships. I mean, when you look Europe and Africa, the only relationship that seems to exist is one of military bases and security…Getting to know each other, that’s the most important thing for me.”

Bringing people together seems to be one of Bombino’s natural gifts. In Europe, North America, Japan, China , Australia , even most recently, Argentina and Chile, the grainy hypnosis of his horizontal grooves, the virtuosity of his guitar style and aerobic explosiveness of his stage shows have hooked a broad gamut of fans ranging from grey - bearded rock and blues habitués, to world - music devotees to young hirsute hipsters - broad enough to include the Rolling Stones, Arcade Fire, Queens Of The Stone Age and the Black Keys (who produced Bombino’s 2013 album Nomad ). Less well known is the fact that back in Niger, his music, which he sings exclusively in Tamashek, the language of the Tuareg , has found favor with every one the country’s many of ethnic groups, a feat of immense significance that no other Tuareg artist has managed to pull off. It could also be a small step in a grand dream - to see Africa regain the cultural, ethnic and economic interconnectedness that Bombino and so many others believe it once possessed before colonialism.

In the meantime, like every Tuareg , Bombino has to struggle with the inexhaustible tensions at the heart of Tuareg culture and society, between tradition and modernity, between tribes and factions. Almost all the songs on ‘ Deran ’ are touched by one or the other preoccupation. His grandparents lived exclusively from their herds, wheeling from well to

well according to season and necessity, far from cities and crowds, free in their blessed immensity. How to preserve the essence of that old freedom, and the culture that went with it, whilst embracing the future, and reaching out to the rest of the world?

That’s the paradoxical challenge embodied in Bombino’s music, and life. ‘Don’t forget / What we know / What we have learned from our ancestors,’ he sings in “Imajghane” (literally ‘the free people’, aka The Tuareg ). ‘My heart is burning! / It burns because of my brothers / My brothers who do not love each other,’ runs the refrains of “Oulhin” (‘My Heart’). How do you preserve achak - the unwritten code of Tuareg dignity, morality and behavior - in an epoch of Facebook, 24 - hour TV, mobile phones and distorted guitars?

Not with a Kalashnikov - Bombino is convinced of that. “For me [taking up arms] is a revocation of the Tuareg ’s future,” h e says. “There are so many problems already. When people revolt, it doesn’t have to be an armed uprising, or a dangerous undertaking. It’s simply a matter of a people laying claim to certain things, and respecting themselves at the same time.” He suggests that the Tuareg should be demanding proper roads (pointing out that Agadez is still connected to the rest of Niger by a slow and treacherous un - paved piste ), encouraging trade, and the ability of Saharans, and Africans more widely, to meet each other, do business, exchange stories, play music. That’s the way forward.

Deran, Deran, Alkheir. ‘Best wishes, best wishes, for peace’. That’s the cry of the woman that graces a Tuareg wedding, that showcase of all that is beautiful, sensuous and homely in desert life. What does Bombino wish for? “We’ re a people who wish for peace,” he says. “ We wish for peace in Libya. We wish for peace in Mali. And we hope that we’re given our due recognition, like all the people in the world who have the right to their own resources, who have the right to their own land.”

Inshallah …if God wills it…as the Tuareg might say.